Were you aware that we only sing the first verse of the national anthem?

And, thank goodness, right? Because most Americans would get bored to tears singing the rest of it. We would certainly mangle the remaining three verses.

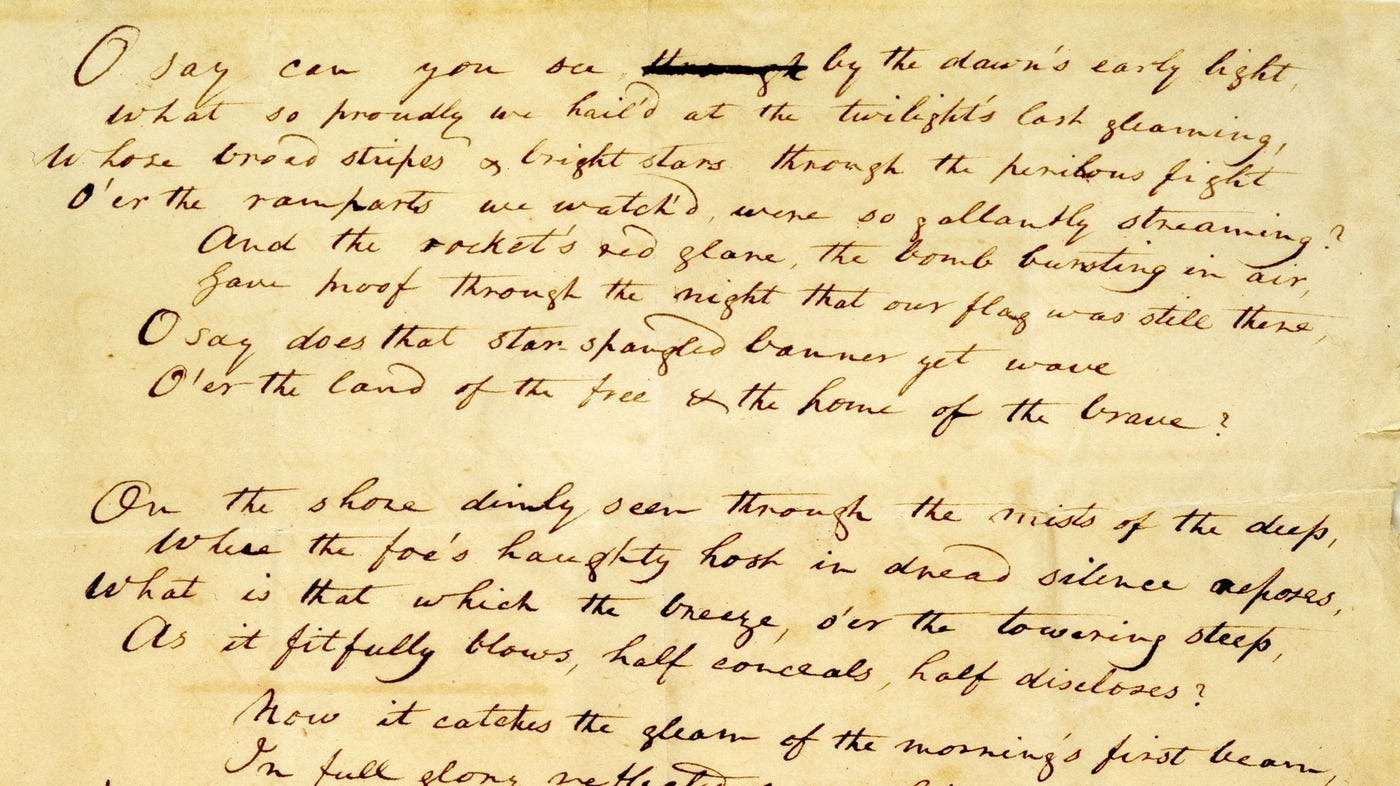

The Star Spangled Banner

Oh, say! can you see by the dawn's early light

What so proudly we hailed at the twilight's last gleaming;

Whose broad stripes and bright stars, through the perilous fight,

O'er the ramparts we watched were so gallantly streaming?

And the rocket's red glare, the bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there:

Oh, say! does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

On the shore, dimly seen through the mists of the deep,

Where the foe's haughty host in dread silence reposes,

What is that which the breeze, o'er the towering steep,

As it fitfully blows, half conceals, half discloses?

Now it catches the gleam of the morning's first beam,

In fully glory reflected now shines in the stream:

'Tis the star-spangled banner! Oh, long may it wave

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave!

And where is that band who so vauntingly swore

That the havoc of war and the battle's confusion

A home and a country should leave us no more?

Their blood has washed out their foul footsteps' pollution!

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave:

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

Oh, thus be it ever, when freemen shall stand

Between their loved home and the war's desolation!

Blest with victory and peace, may the heav'n-rescued land

Praise the Power that hath made and preserved us a nation!

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just,

And this be our motto: "In God is our trust":

And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

Before this morning, I had never read The Star Spangled Banner in its entirety and, if I did, I did not give it a second thought. I can’t remember if it was taught in the history lessons I received but, if it was, the poem and the story around it, left no indelible impression on my mind.

For example, I somehow imagined it was written in relation to the Battle at Fort Sumter or, basically, the beginning of the Civil War when South Carolina forcefully seceded by firing on a United States garrison. But, no, it wasn’t written about Fort Sumter, it was written half a century earlier about one of the battles of the War of 1812.

Apparently, Francis Scott Key wrote the poem in 1814 about the Battle at Fort McHenry which was one of the conflicts during the War of 1812 where America was attempting to annex Canada and Britain responded by essentially saying, “Hell, no!” There was also a brouhaha going on over the interdiction of ships, and the conscription of American sailors for the British Navy and, of course, the English were also in a spat with France.

The original title of the poem which was printed in a Baltimore periodical by ‘Anonymous’ was “The Defence of Fort McHenry”.

The tune that we use for singing the Star Spangled Banner was borrowed from the British Anacreontic Society called “To Anacreon in Heaven”. From what I gather Anacreon was a Greek poet who liked his poetry light, jovial and festive. Merriam-Webster says that anacreontic means “in the manner of Anacreon, especially, a drinking song or light lyric.”

Take of that as you will.

During the war, naturally, runaway slaves sought their freedom when coming in contact with Britain’s invading forces, as at Fort McHenry which was a large scale maritime action. So many now ‘former’ slaves joined the naval forces, they were formed into a unit known as the Colonial Marines. Historians estimate over 4000 slaves sought refuge, or fought, with the British.

Following the War of 1812, that ended in a stalemate, America’s slaveowners petitioned England for reparations due to loss of “property” (the 4000 slaves) or the return of their “property”. The request was ignored and the Blacks who joined the Brits sailed to Trinidad, a British colony, and were given 16 acres of land. To this day, they’re referred to as “the Merikans”.

As it turns out, Francis Scott Key was a slaveowner himself, though it sounds like he was a more ‘benign’ slaveowner unlike the more malignant type of slaveholder like, Simon Legree, of Uncle Tom’s Cabin fame. Here is what Britannica had on the author of our national anthem that began its life as a poem:

After he wrote the patriotic poem that would become the U.S. national anthem more than 100 years later, Key continued his law practice. He also became involved in colonization efforts, helping to found (1816) and promote the cause of the American Colonization Society (ACS), which worked for decades to send free African Americans to a colony on Africa’s west coast (later the country of Liberia). The ACS was reviled by abolitionists and by many free blacks as little more than a vehicle to rid the United States of African Americans. Key used his well-honed oratorical skills to recruit new members, raise money from private individuals, and lobby Congress and state legislatures for funds.

Key was also an early and ardent opponent of slave trafficking. Although he was a slaveholder from a large slave-owning family, he treated his own slaves humanely and freed several during his lifetime. He provided free legal advice to slaves and freedmen in Washington, D.C., including civil actions in which enslaved individuals petitioned for their freedom.

Although Key had abstained from politics for most of his life, he became a strong supporter of the Democratic Party and its candidate in the 1828 U.S. presidential election, Andrew Jackson. After serving as a trusted adviser to Jackson for his first years as president, in 1833 Key was appointed U.S. attorney for Washington and served in that position until 1841. Key also became a member of Jackson’s “kitchen cabinet,” a group of close advisers who did not hold official cabinet positions but who met frequently with the president.

Between his slaveholding, his shipping them back to Africa inclinations and his intimate relationship with Andrew Jackson, you would have to say Key was “complicated”.

At the very least.

When he wrote his poem that became a song that became America’s national anthem set to the tune of what might have been a drinking song, slavery was the law of the land. Just about every well-to-do white man below the Mason-Dixon Line held slaves as property.

Which is why lines 5 and 6 in the third verse are, or should be, problematic for 21st century America’s sensibilities and sensitivities.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave

Francis Scott Key was rhapsodic over the fact he could see the flag still waving above Fort McHenry after a night of bombardment. (I learned that the ‘rockets red glare’ was a bit unusual and due to a new-fangled munition the British were putting to the test.) And he was also waxing poetic about the plight of those who opted to escape towards freedom. In his view - he was an attorney after all - they were breaking the law. In his view, they were somebody’s ‘property’.

I know. Times were different then. America moved on. Abraham Lincoln emancipated the slaves. All of that was a long time ago and the societal narrative of 1812 is so different more than two hundred years later.

But, here’s the kicker. America didn’t adopt this national anthem until 1931.

What was going on in the world, in America, in 1931? The Nazis in Germany were on the rise. Benito Mussolini, the Italian dictator, was in power and was being denounced by the Pope. A spate of lynchings of Black Americans was just beginning to abate. ‘Jim Crow’ laws were in full effect with no sign of going into decline.

Chances are the mostly patriotic words of the Defence of Fort McHenry just slipped underneath the radar of white privilege when Congress argued for its acceptance as the national anthem. It’s adoption needn’t necessarily have been nefarious. Or a thinly veiled dog whistle from the dog whistlers of the day.

Still - being armed with that information about our national anthem - doesn’t it lend a bit more credence as to why a Black professional athlete might decide to make that the hill they are willing to die on? Or shred their reputation upon? Or to suffer being blackballed?

The national anthem, never intended to be the national anthem to begin with, seems to me to be the perfect symbol for a non-violent protest against racial injustice. A respectful, non-violent protest.

You want to know how I got down this particular rabbit hole?

I saw something about how Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg told Katie Couric in an interview that she thought Colin Kaepernick’s protest was “disrespectful and stupid”. During this same interview she had called the one I refuse to name “a faker”.

She later apologized for both comments as statements demeaning to her position as a U.S. Supreme Court Justice.

She also said this:

Some of you have inquired about a book interview in which I was asked how I felt about Colin Kaepernick and other NFL players who refused to stand for the national anthem. Barely aware of the incident or its purpose, my comments were inappropriately dismissive and harsh. I should have declined to respond.

I was suspicious she would have said such a thing, so I began my internet sleuthing. Which led me to a deeper analysis of the national anthem itself.

What better activity on a gloriously rainy afternoon than grouting the cracks of my crack-filled American history?

###

AAR, Cathy Hollingsworth, a friend from high school, sent along this stellar suggestion for a movie - should you be racking your brain for what to watch next. The title is Summerland and I don’t believe you will recognize any of the actors except perhaps the older woman at the very beginning. I found it very compelling. Compelling enough for it to cause all the other things going on in my mind to shut the hell up. So - effectively - giving my mind a rest. You will have to rent it from Prime and be sure not to mix it up with the Netflix series of the same name. If you watch, I hope you enjoy it as much as I did!

Also, another AAR, Steve Laboff, who, after 40 years has become a full fledged dog lover and, I know this, because I am watching the life and times of River, his mostly German Shepherd rescue mutt, on Facebook practically in real-time, posted a non-dog video of climbers at the apex of the Matterhorn.

For some reason, it feels like the perfect metaphor for 2020.

Otherwise, please share with your ten thousand closest friends. Thank you! - JLM

I think they only taught Texas history.