My last Grand Canyon river trip was in the fall of 2017. The participant list included the usual suspects - a transient ER doc, ski bums filling in time before the winter snow fell, one retiree from the public school system, health care workers and soon-to-be health care workers, a vacationing fireman. Almost all were river guides, former river guides or guides of some sort or the other.

Including the odd man out.

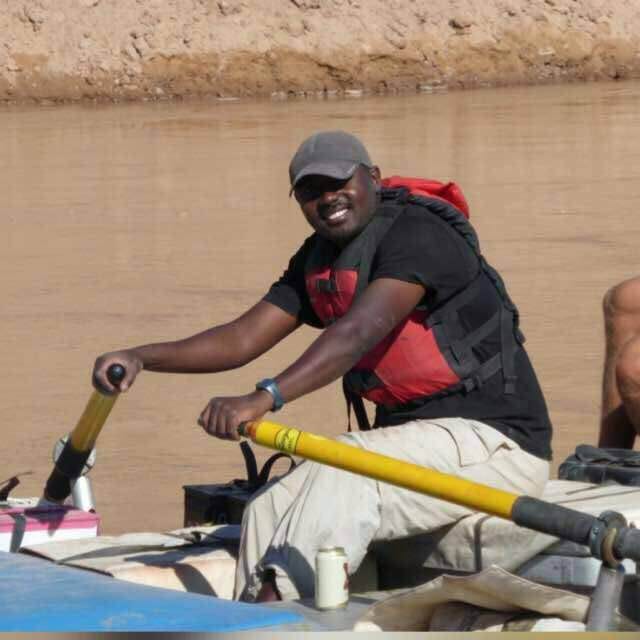

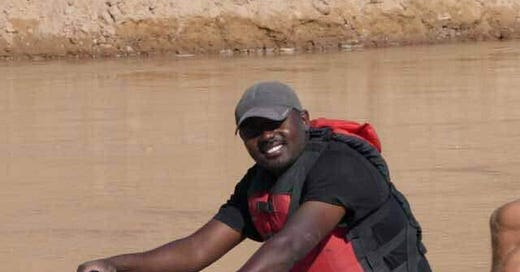

Thomas Joseph from Tanzania.

He pronounced it, “Tahn-zahn-nee-uh.” Emphasis on the “zahn”.

Thomas Joseph was as dark as a well seasoned Dutch Oven and, when he smiled, which was often, your day was much brighter for it. He was also earnest, helpful, considerate and playful. All sought-after traits in guides of any sort. He had no trouble fitting in with our motley troupe.

In Tanzania, he worked as a mountain and safari guide on Kilimanjaro and in the Serengeti. He studied Wildlife Conservation at the College of African Wildlife Management-Mweka. He went through paramilitary training in college as part of the Wildlife Management program and it gave him the tools to battle the poachers of African wildlife.

He was a good guy, as well as guide, in every way.

His English was superlative but, every now and again, something would get lost or misconstrued in translation. He seemed very much a man at ease, even though there were a couple of colossal misunderstandings before he ever reached Lee’s Ferry, the launching point for raft trips down the Grand Canyon.

The group leader had worked with Thomas while climbing Kilimanjaro and had helped sponsor Thomas’ first foray to the United States. The Grand Canyon float trip was to be just one part of a multi-month tour across America where several of his clients would assist in hosting his stay. This is all as part of an explanation for why Thomas might not have realized he would be on the river for three weeks. A typical Grand Canyon trip length.

The Canyon trip was just one segment of an ambitious itinerary.

So, it came as a bit of a surprise to him that he would be incommunicado - no internet connection - for practically a month.

And, then, apparently, he had not envisioned self-propelled inflatable rafts for the adventure he was about to undertake. He was imagining a “cruise” of some kind. Something perhaps like this:

I was not there when Thomas learned about some of these misconceptions, but I understand he took it all in stride. By the time I initially met him, if he was worried, he gave no indication of it. His good sense of humor remained intact along with his smile. At Lee’s Ferry, as we were readying the rafts, the trip leader assigned Thomas, who had no river skills, to a raft to be piloted by a very competent and gregarious second year river guide, Matt.

But there was one more thing Thomas had not revealed to us.

He did not know how to swim. Not a stroke. Not a crawl stroke, not a back stroke, not a butterfly. Not even a dog paddle.

In high school, a buddy of mine wanted to find out if it were true that the type of bulldog he had could not swim. It was very much true. Buster sank like an anvil.

Thomas’ response, without a lifejacket, would have been similar to Buster's. Having grown up in a country where there were many things in the water that might eat you, Thomas had never learned to swim. It’s not really that surprising if you consider hippos, crocodiles and god knows what else might be lurking beneath the surface.

And now, he was launching on to the grandaddy of all river trips - 250 miles and hundreds of rapids and powerful currents - in an eighteen foot inflatable raft manned by a fresh-faced, tow-headed greenhorn for nearly a month with a bunch of people he had only been introduced to the night before.

And he couldn’t swim a lick.

At more than one of the ominously big rapids we stopped to scout, I sidled up to a nervous-looking Thomas, (but still smiling, of course), and I would say I was more than happy to have him join Molly and I in our raft. I would leave him mulling over the idea, staring at whatever maelstrom of whitewater we were currently scouting and return to my tethered raft.

Moments later I’d see him picking his way back upriver through the tamarisk and I’d say, “Well? Will you be joining us?” And he’d respond in his most serious demeanor, “I must stay with Matt. He needs me.”

And he would ride in the bow of their raft through whatever frothing monster we were encountering that day - House Rocks, Hance, Horn Creek, Hermit - exhorting Matt on to glory, or throwing his weight around as ballast or just hooting and hollering. He and Matt had impeccable runs all trip long. Thomas never involuntarily ‘took a swim’.

By trip’s end, Thomas was rowing intermediate rapids with confidence and even rowing long, tedious stretches of flat water, where the trick is finding and staying with what can be an imperceptible current, while keeping up with guides who had decades of experience.

And, when all was said and done, he still couldn’t do a crawl stroke to save his life, but thanks to his perseverance, along with a couple of members of the crew, he managed to master a pretty mean dog paddle.

###

I haven’t forgotten about the pandemic. I just thought telling Thomas’ tale on the Grand Canyon would be a nice break.

But, if you need some ammunition for all the misinformation, try these two articles both brought to me by alert reader Steve Ell:

Remember Prom Night? We spoke of it days in advance as the excitement grew, only to learn that Thomas thought we were preparing for prawn night. Well, there was that lobster thing, and I guess prom is not so big in Tanzania.

All true! Wonderful portrait of an all-around good person.